Simon(e) van Saarloos: Urning for Everyone

For the exhibition Urning & Urningin. Language and Desire since 1864 guest curator Philipp Gufler invited three writers to reflect on the legacy of Karl Heinrich Ulrichs: Simon(e) van Saarloos, Hendrik Folkerts and Gürsoy Doğtaş. You can read them here, or in our exhibition zine Nesting Habbits.

- Simon(e) van Saarloos

Urning for Everyone

Karl Heinrich Ulrichs is hailed as a granddaddy for European gays like Sappho is the founding mother for many European lesbians. Where Ulrichs was (of course wrongfully) labeled the first gay man in world history by activists in the 1980s, Sappho is often claimed as the first recorded lesbian. In his 19th century writing, Ulrichs conveyed that queerness was natural and inborn, way before the neuroscientists of the 1990s popularized the belief that sexual orientation is mapped and predetermined in the brain. Those who reside on the Greek island of Lesbos – where Sappho was born and lived between circa 610 and 570 BCE –– are called Lesvians. Lesbians have been proud Lesbians (with capital L!) by birth for centuries.

On Lesbos, I take a walking tour with the director of the documentary Lesvia, which follows the 70s increase of lesbian tourists arriving in the village of Eressos, and the co-habitation and conflict with locals. As she points to the “boob shaped” mountain (reminding me of the “clitoris hill” in San Francisco’s lesbian neighborhood Bernal Heights – a woman and a beautiful landscape are always also just some sites to tramp on), she says: everyone wants a piece of Sappho. Tourists, locals, historians, poets, different generations of lesbians and dykes: they all need Sappho to be what they want her to be.” Yes,” she continues, “the record shows certain facts: Sappho was from an aristocratic family, and she had slaves, yes, we know this, but her life has to be understood in its own time.” The tour group nods righteously, and I decide to leave. Not because I think Sappho should be deplatformed for being who she was in her own time, but I do question the defensive pretense to understand a time that is apparently morally particular but still can be comfortably defined from the future. I can’t quite join a chorus that’s protecting a historical figure against supposedly contemporary views – especially as these views are also contested as killjoy in the current moment, which makes it easy to imagine that oppositional ideas from the past might not have survived the eradicating forces of selective archives.

It is also possible that my quiet departure from this group has something to do with being the only person there who is perceived to be a man. Of course, masculine off-center vibes are abundantly present among this lesbian crowd, but my hormonal transition has superficially landed on some blonde surfer boy situation, and despite my Urning gestures and Babygirl purrs, it’s the boy and the boy appearance alone that is seen. The possibility of appreciating the impossibility of feeling close to the real Sappho while also only being able to know her through one’s own framework and desires, relates, for me, to the appreciation of the impossibility of having both a pussy and a cock at the same time. The love for impossible combinations is acquired taste and, on this island, dickgina is only appreciated by some. This is not a commentary on lesbian separatism. Most separatism has loose ends, and most loose ends crave to be pulled, no matter how carefully this must be done. It might be frustrating to focus on low hanging fruit, but if you pluck with enough passion, it won’t grow back until next season.

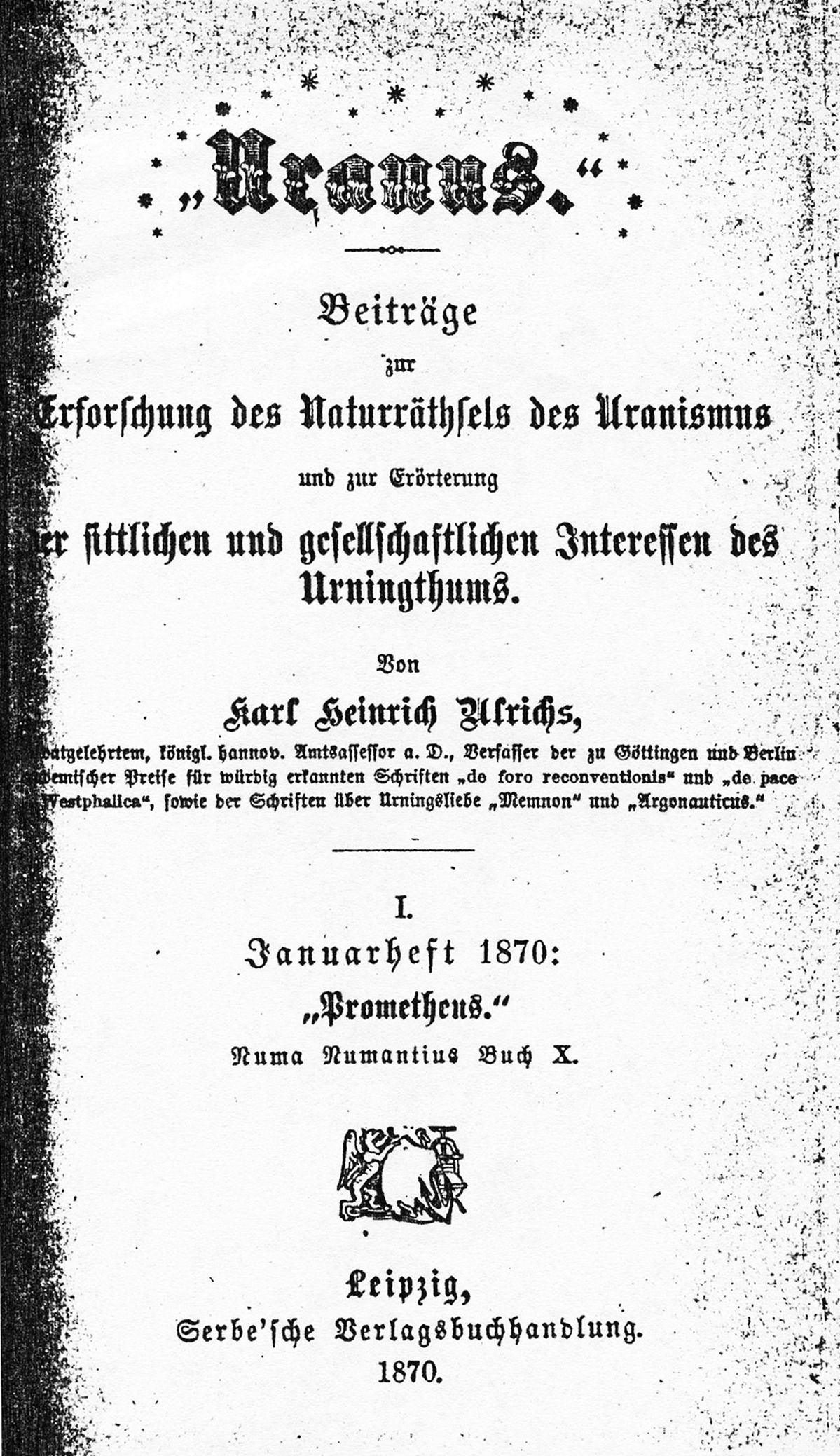

Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, cover van het magazine Uranus, gepuliceerd in 1870.

My appreciation of impossibility – the impossibility of “more and more” as trans life might show us,1 or “the particular play in the space of impossibility that blackness is"2 – is about reading historical figures. Figures such as Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, figures such as Sappho. We do not leave or disengage from the archives (like I did on the tour) just because it is impossible.

It is on Sappho’s Island that I read through the more than eight hundred pages of Ulrichs’ Research on the Riddle of Man-Manly Love. It is on this island that I pay twelve euros an hour to gym with a personal trainer – a luxury I have not been able to afford anywhere else. He is my height but huge in width, his muscles bulk from every angle. And he is incredibly friendly, gentle even. On one of our first sessions, he asks me about the scars across my chest and when I tell him I’m trans, he responds like everyone else in the gym by saying that I’m so strong, you would never know. Little do they know that, to cite Ulrichs, “Even if I have a man’s beard, limbs, and body ... I am and remain a girl” and proudly so.3 The trainer wants to know if he should consider moving to the US to compete athletically. When I wonder aloud how it would be to migrate there now, considering Trump and the hold of fascism on daily life, he nods understandingly. He shows me pictures of different haircuts and asks what would look good on him, especially as he worries about his receding hairline. He exposes his forehead and, invited in, I study it up close. I tell him that in the US, people take drugs for most things, including balding. He asks me to send him information about these pills, and this is how we start following each other on Instagram. When Charlie Kirk gets shot, the trainer posts a video celebrating Kirk’s heroism. He also shares posts about Trump warning for the ruination caused by immigrants.

It is on the island that I write this, not far from where Sappho allegedly jumped off a cliff overlooking the Aegean Sea. The rock I’m looking at must have been her last view. It’s a few hundred meters offshore, a fifteen-minute swim from here. Except, my swimming is terrible, and it takes me much longer. As a kid, I hated the swimming classes that are a mandatory part of growing up in The Netherlands. To fit my transition story, I have re-narrated my distaste for swimming as a result from having to wear a bathing suit, but in reality I only remember the one time that my mom had forgotten my bathing suit (a mother is always also just a site to blame), and I had to wear shorts from the pool’s lost and found. While waiting for the coach’s whistle to jump in, peers were nagging me, asking if I was a boy or a girl. With my buzz cut and baggy clothes, I was always such a boy – to the extent that on holidays I’d make new friends as if I were one –, but this naked display felt really embarrassing. Maybe the problem was that I had to wear these shorts out of necessity, and gender out of necessity never seems to work on me.

Despite being a terrible swimmer, I have struggled to make it to the rock, because a local legend claims that if you touch it, you become gay. The rock’s magic has been proven by proxy, because most people who come to Lesbos are gay already anyway. However, I believe in the rock, like I believe in fire. In attempts to understand my experiences with sexual assault at a young age, I perceive both the assault, myself, the perpetrator, the wound, the entangled dance with the pain and pleasure of the happening, as fire. Nothing stays the same, once touched by fire. But the touch also diminishes the distance, the reach between one separate element and another: what gets burned by fire, also partly becomes fire. Like anything that enters us – whether classified as toxic or not –, we also become it, inseparably linked and co-created. What I love about perceiving the rock as a gay making entity, has thus little to do with ecosexuality or a celebration of nature’s force. What I love about the rock as a magic gay intoxicator, is the (im)possibility of no longer perceiving sexuality as inherent or individual. It is a rub, a touch, a belief, a myth. It is not, like Ulrichs argues in defense of Urnings and Urningins rights, our own personal nature. Nor do I mean to say it’s just nature itself. I don’t mean to argue for the existence of queerness at all! Not even in penguins, or seahorses, or in anthropological excavations or historical recuperations. Inspired by Ulrichs etymological reference to the planet of Uranus, I wish to displace the idea of queer so far outside of us, that it requires no defense at all. I’m imagining an existence without defense. An existence of gay because a rock has been there for centuries. Because fire burns. Because toxins enter us and we are toxic. Because the world is a viral and contagious place. I wish for a gay that does not need to be happy or specific, a trans that does not need a book or record. A queer that lives free, because a river and a sea can hold each other near, without the violation of illegal occupation.

I have come to this island from another one, Turtle Island, also known as North America. Upon arriving there, the friends I was staying with lost their grandchild, as he tried to shoot his High School classmates before taking his own life when the cops arrived. This particular school shooting was barely covered in the news, because Charlie Kirk was killed on the same day, while being asked about the number of mass shootings in the US. To distract ourselves, we played a game of charades. We were giddy, the air thick with desperation and the comfort of creating a system of meaning together. It was my turn to perform and gesture while the others guessed and I pulled a book from the hat full of references: Just Kids by Patti Smith. I started with the second word – kids –, got on my knees and made playful sounds. It took a while for my friends not to call me “drag” or “gay” or “a horny animal” and instead correctly guess “kids”. Then, I pretended to be blindfolded, holding two scales. To get to the word “just”, I was mimicking the lady of justice. But no matter how much I swung the imaginary scales and re-emphasized the blindfold, they did not guess “justice”. Perhaps the lady of justice is a historical figure now, too far off from the current US American situation to serve as a reference in a game. To gesture both kids and just(ice), it would have been most efficient if I had pretended to hold a gun. What is of interest to me here, is not to sketch the US as a pitiful place, a ground zero in contrast to Europe’s moral soil. Instead, I’m interested in the complete eradication of justice as we know it. What report would Ulrichs – a trained lawyer who addressed the Association of German Jurists, advocating queer life – write about Urnings and Urningins, if it had not served as a defense of legal rights? Without depending on a legal system that can either ruin or recognize our existence, what kind of Urning life would we have learned about?

In the meantime, Trump claims that the Left wants transgender for everyone. I wish. I wish we had a Left like that. I read a similar expectation and desire for contagion in Ulrichs when he writes about the statistics of gay life: “the ratio of adult Urnings to adult males is 25,000 in 12,500,000, or 1 in 500. That is, for every 500 adult males in Germany there is an average of one Urning.” He also detects a rapid onset of gay desire: “the number of Urnings is constantly increasing.”4 This increase came true, though we have been stuck at 10% for a while now. Such statistics are meant to discursively contain us, but we who roam the alleys and meet the downlows and feed the hunger of the flexibles, we know this calculation means nothing.

I choose to see a contagion strategy in Ulrichs description of the Urning and their relationship to women, which sounded a little different than his approval and praise of femininity. When he writes that the Urning is “born to love men and horrified by women,”5 I (choose to) see a contagion strategy aimed at hetero (Dionings) men. By claiming the supposed disgust of women as a particular gay quality, Ulrichs moves toward what binds straight men always already: the hatred of women, no matter how much they desire them as well. If loving men and feeling horrified of women is a quality of homosexuality, straight men are basically already there. Focusing on the gay man’s love for men and disdain of women, is a propagandist way of making straight men gay. This is what I call a queer reading of the archive: not by seeking historical figures who were queer or queer adjacent, but by pressing queerness onto everything I come across. It’s a self-obsession that becomes so omnipresence, that the focus on self nearly disappears and instead makes of trans and queer a contagious everywhere.

If I can get what I need from Trump (“transgender for everyone”) I can get what I need from Ulrichs. And I hope you do too.

1 More and more here refers to a transcribed conversation between psychoanalysts Avgi Saketopoulou and Griffin Hansbury titled “Sissy Dance $1: The More and More of Gender” for The Psychoanalytic Review, Vol. 109, No. 3, September 2022. The more and more counters an economy of conservation and scarcity and instead embraces abundance. This abundance also shows up in the trans ability to hold the material and the symbolical body both at the same time, even if they are considered to hold different or opposing meanings and functions. Abundance has been an important framework for my work, whether in my book on memory culture and the (im)possibility of commemorating everything all at the same time (Take ‘Em Down. Scattered Monuments and Queer Forgetting), or in my exhibition ABUNDANCE. We must end the world as we know it, co-curated with Vincent van Velsen at Het HEM, Zaandam 2021.

2 This is a citation from Fumi Okiji’s 2025 book Billie’s Bent Elbow: Exorbitance, Intimacy, and a Nonsensuous Standard for Stanford University Press, in which she celebrates the “particular play in the space of impossibility” as a Black practice and ability to let opposites exists without trying to conflate, flatten or relate them. The dissonance between opposing ideas, feelings and materialities does not have to be solved. Instead, practicing a comfort with discomfort means that impossibility can exist without evoking a stressed or disturbed response.

3 This translation comes from Philipp Gufler’s book Dis/Identification, Kunsthalle Mainz, 2024. I prefer Gufler’s translation from German over the published English translation: „My beard is a man's, my limbs and body virile; However, inside: I am and remain a female.“Ulrichs, Karl Heinrich. The Riddle of “Man-Manly” Love: The Pioneering Work on Male Homosexuality. Trans. by Michael A. Lombardi-Nash. Buffalo, N.Y: Prometheus Books, 1994, 99. It was published in Latin in „Inclusia“: „Sunt mihi barba maris, artus, corquesque virile, his inclusa quidem: sed sum maneoque puella., which was translated into German „Hab ich auch den Bart auch vom Mann, die Glieder, den Körper, das alles schließt mich von außen nur ein: Ich bin und bleibe ein Mädchen“ by Wilfried Stroh (in: Wolfram Setz (ed.): Karl Heinrich Ulrichs zu Ehren. Materalien zu Leben und Werk. Wilfried Stroh, „Karl Heinrich Ulrichs als Vorkämpfer eines lebendigen Latein“, Verlag rosa Winkel, 2000, 85.

4 Ulrichs, Karl Heinrich. The Riddle of “Man-Manly” Love: The Pioneering Work on Male Homosexuality. Trans. by Michael A. Lombardi-Nash. Buffalo, N.Y: Prometheus Books, 1994, 23.

5 Ulrichs, The Riddle of “Man-Manly” Love, 25.