Listen in every way possible, to everything that is possible to hear (part I - III)

- Eva Burgering

‘Listening is directing attention to what is heard, gathering meaning, interpreting, and deciding on action,’ wrote composer Pauline Oliveros (1932–2016) in 2010 to highlight the difference between hearing and listening. For while some may consider these two words synonymous, for Oliveros there lay a whole world within the distinction between hearing and listening. In this distinction, a universe of possibilities unfolded for her, where everyday sounds were elevated to the most exquisite soundscapes. The roar of the wind or the dripping of water, in this universe, were as virtuosic as Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. For Oliveros, it all began on her twenty-first birthday when she received a tape recorder as a gift from her mother. She began making recordings in her room and listened back to them with astonishment: the tape recorder picked up so many more sounds than she could hear with her own ears. This revelation – the world of sound that had until then gone unnoticed by her – led her to listen as attentively as possible to everything around her from that moment on.

This fascination with attentive listening formed the core of Oliveros’ work and life from that moment until her death in 2016. The idea of listening not only to sound that is meant to be heard (such as music), but to all sounds (such as your own thoughts or to nature), was developed into a method she called Deep Listening. Through workshops, listening exercises, and books, Oliveros documented her ideas to make them accessible to everyone. She believed that anyone could develop listening skills to hear themselves and their surroundings in a different way. Collectivity played a major role in this: her ‘listening recipes’ were often meant to be undertaken in groups, and she frequently performed for groups with her Deep Listening Band. She viewed listening as an active act that shapes cultures and can bring groups of people together.1 For Oliveros, listening was inherently political and social.

When President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in 1963 and the Vietnam War reached its peak, Oliveros felt unmoored. She withdrew and no longer wanted to perform. It was listening that lifted her out of this slump: she founded the feminist ensemble ♀, through which she developed ‘sonic meditations’ in response to the war. With titles like ‘Teach Yourself to Fly’ and ‘Have You Ever Heard the Sound of an Iceberg Melting?’ they created exercises aimed at increasing one’s engagement with the world around them. These meditations were not intended as escapism or a getaway from political misery, but rather to sharpen one’s perception of this reality. In June 2016, shortly before her death, Oliveros led one of her last meditations, the Tuning Meditation, for around five hundred people in London in response to the outcome of the Brexit referendum. Many people were unsettled by the result – the United Kingdom would leave the European Union – and gathered together to find solace with Oliveros. Oliveros led her meditation – ‘Listen with your mind’s ear for a tone’ – and together, the five hundred people attuned their voices to each other, creating a single, collective, comforting bath of sound.

By truly (and collectively) listening – to sounds, voices, the world – there is the potential to deepen one’s engagement with one’s surroundings. Thanks to Oliveros, the practice of attentively listening to all the sounds in the environment, including silence, became a popular method worldwide and continues to inspire many composers, musicians, and artists to this day. Especially in this time of continuous saturation and distraction, attentive listening seems to be a radical act in itself. The question Oliveros raised with her method more than fifty years ago – what happens when you listen attentively rather than merely hearing – forms the starting point for the new programme at Nest in Laak. Art and listening in the broadest sense will be explored by artists in successive chapters. The emphasis will not be on the technical aspects of sound or music, but rather on the social and societal impact of paying attention. Listening involves much more than merely hearing sounds; it requires a specific focus and a way of paying attention that engages all your senses.The body is not just a passive receiver but actively participates as an instrument within a larger orchestra of architecture, sound, light, moving images, and brushstrokes. This is what Oliveros meant by the ‘listening effect’: ‘What is heard is changed by listening and changes the listener.’2

From the belief that artists, more than anyone else, can respond to and reflect on a constantly changing society in a critical, moving, or empathetic way, Nest has developed (group) exhibitions over the past sixteen years to provide space for a wide range of artworks, research, and perspectives. Since March 2024, Nest’s permanent space, located on the ground floor of the DCR-building at De Constant de Rebecqueplein, has been undergoing renovations by the municipality, with the goal of delivering it completely climate-neutral by 2025. Therefore, Nest has moved to a new location: an old warehouse, adjacent to the nightclub and bar Laak, under the name Nest in Laak.

This new location is in many ways the opposite of the old Nest: a dark space, with a nine-meter-high ceiling and a thick concrete floor. Here, Nest is experimenting with the new program line centered around art and listening. Instead of the group exhibitions around a theme, which Nest is well-known for, only one artwork or installation will be presented at a time, allowing you to fully experience the work with complete focus. In each exhibition, artists, designers, performers, and musicians, either solo or in duos, take over the space and respond to the context and theme of listening and sound. Topics such as the fragility of democracy, climate concerns, gentrification, the changing city, and tributes to female pioneers in electronic music, as well as club culture and fashion, will be explored. The exhibitions are not only on view during the day but also late into the night during Club Laak’s club nights.

Even in this new context, Nest remains grounded in what truly moves it: listening to society and artists. It also involves stretching the boundaries of disciplines that often inhabit different stages. Traditionally, we view music and theatre performed on stages, and art displayed on flat floors – often referred to as the ‘white cube.’. The unwritten rules differ here: in an art space, you move freely and choose your own time, whereas the performing arts usually have a defined beginning and end. At Nest in Laak, next to a lively nightclub, we are creating a space that bridges these disciplines and behaviors, bringing together art, music, and performances. The so-called Ear Piece evenings will play an important role in this. Named after a listening exercise by Oliveros, these monthly evenings revolve around the convergence of different art forms.

With Oliveros’s words in mind – ‘Listen in every way possible, to everything that is possible to hear’ – Nest in Laak transforms into an artistic listening arena where all voices and sounds may be heard, listened to, and experienced.

Polyphonic Voices

May/June 2024

Artist Henk Schut has been collecting sounds for years. The recordings he has amassed and stored in his seemingly inexhaustible sound archive are showcased in his overwhelming installations, where this multitude of sounds takes centre stage. One of these installations is The Singing Parliament, where 150 voices and sounds converge in a sonic landscape. This landscape is formed by custom-made speakers, which Schut designs himself using leftover materials such as PVC pipes or surplus wooden panels. The speakers thus become individual characters in his parliament: some are tall and slender, grouped in clusters, while others are robust and placed on a reclining platform. Each speaker emits a unique sound. Some sounds may be recognisable: the gentle chirping of birds, the bubbling of water, as well as piercing protest chants or the crossing roar of a flying F-16. The speakers sometimes play simultaneously, or at other times, only a few can be heard. Together, they create a vibrant landscape that you can walk through, lie in, or wander around.

Schut did not choose the number of speakers by chance: the 150 sounds refer to the Dutch House of Representatives, which has the same number of seats. Just as in a democracy, the sounds in The Singing Parliament sometimes come together harmoniously, while at other times they are drowned out or clash with each other.. Similarly, in the House of Representatives, many different opinions, sounds, and voices coexist within one democratic body.. Nevertheless, Schut prefers that you enter his parliament without any prior knowledge of this reference, without any political bias. The sounds in the installation are open to interpretation: all associations are welcome. However, the installation does contain references to political protest; attentive listeners may hear protest chants from the Black Lives Matter movement.. The core of the installation is formed by a circle of five speakers, from which the musical piece Deus venerunt gentes by composer William Byrd is played.

Byrd wrote this piece in the late sixteenth century, when the Roman Catholic faith was banned in England. In the psalm, Byrd critiques war and the destruction of holy places, a message that remains strikingly relevant today: ‘They have poured out their blood / as water round about Jerusalem / and there was none to bury them.’ The text can also be read with a double meaning, as an expression of the religious and political tensions in England at the time. Byrd, a Catholic himself, used the power of music to express his voice, despite the risk of persecution. The piece was recorded a cappella by singers from the ensemble I Fagiolini. The crystal-clear, pure voices create a poignant sense of vulnerability within the installation, even though the Latin text is not literally comprehensible. In this way, Schut seems to be saying: even if you do not immediately understand one another, listening can still move you and evoke an emotional response.

Henk Schut’s installation raises questions about democracy and coexisting in general. Whom do we listen to, which voices are heard, and which are suppressed by governments, authorities, violence, or (self-)censorship? It is the plurality of voices that The Singing Parliament revolves around: both human and non-human sounds. Schut explicitly gives a voice to the non-human, such as with the sound at twice the frequency of the Earth’s crust, which can be heard by pressing your ear against vibrating copper plates. This reflects his concerns for both humanity and nature: these different sounds are not to be taken for granted. This becomes clear when the F-16 roars through the space every few minutes, demanding all attention with its deafening roar.

Schut’s installation beautifully reveals the potential of polyphony. Polyphony is a musical term referring to a compositional technique where multiple independent melodic lines, often of equal importance, are played simultaneously. Polyphonic music may sound strange or discordant to the modern listener. ‘We are used to hearing music with a single perspective,’ writes anthropologist Anna Tsing in her chapter Arts of Noticing.3 Tsing learned to appreciate polyphonic music as an assemblage made up of different parts:

‘[…] rather than limit our analyses to one creature at a time (including humans), or even one relationship, if we want to know what makes places livable we should be studying polyphonic assemblages, gatherings of ways of being. […] In contrast to the unified harmonies and rhythms of rock, pop, or classical music, to appreciate polyphony one must listen both to the separate melody lines and their coming together in unexpected moments of harmony or dissonance.’ 4

This is what Schut shows us with The Singing Parliament: although each speaker in his installation operates independently and produces its own sound, the 150 voices must collaborate. For when someone enters the installation, it becomes a single landscape of sound for the ear of the listener.

Ecological Attunement

September 2024

What would the Earth sound like if humanity went extinct? This question is central to Nikita Gale's installation, DRRRUMMERRRRRR. Gale imagines this future scenario by positioning drum kits in such a way that no human could play them. Instead, the drum kits are played by water, which has the power to bring the entire installation to life. With winding hoses and pipes, the water flows over the cymbals and drum skins. Gale seems to be saying: whatever humans create or design, nature will ultimately prevail. In a sense, this might be true: when the Earth becomes too cold, too hot, or too unpredictable for humans to inhabit, humanity may perish, but the planet will continue. Just as weeds have the ability to grow through asphalt, Gale invites us to embrace humility. ‘No one owns the ocean,’ writes Gale as an accompanying statement to one of the first presentations of the installation.

Gale is interested in the role of technology in a post-humanist world. What happens to objects like drum kits when there are no humans left to interact with them? What kinds of intriguing and exciting scenarios does this evoke? The way Gale plays with this future scenario is reminiscent of how writers like Octavia Butler and Nora K. Jemisin use science fiction and (Afro)futurism to highlight social issues such as gender, capitalism, and ecology. In science fiction books, such themes and theories were often explored fifty or sixty years ago and remain relevant today. Gale, therefore, sees science fiction as an intriguing means of exploring and gaining knowledge. One reference the artist cites is The Sound Sweep (1960) by J.G. Ballard, a dystopian short story set in a future where sounds become tangible entities that must be cleared away, resulting in, among other things, soundless music.

Gale sees a clear link between sound, silence, and political structures, envisioning an important role for pop and rock music. It is pop music—think of sold-out stadiums of pop stars—that, according to Gale, reflects what society values and what people want to focus their attention on. And what people focus their attention on, Gale argues, is closely tied to capital, money, and power. Pop icons like Tina Turner are therefore, for Gale, not only significant sources of inspiration but also symbols of this representation of power in popular culture. In the work PRIVATE DANCER, Gale uses elements of a pop stage—the familiar aluminium truss structures—and Tina Turner’s 1984 album Private Dancer. However, no sound can be heard: the lights flash precisely to the melodies of Turner’s album, but the music itself is absent. This raises the question: what remains of a performance when the music is removed? Can it still be seen as a performance, can it be listened to? As a reference to Ballard’s The Sound Sweep, Gale examines the phenomenon of a performance and silence as a political gesture.

In DRRRUMMERRRRRR, another dystopian future scenario takes centre stage: one in which climate change has led to the downfall of humanity. This evokes thoughts of Octavia K. Butler's 1993 novel Parable of the Sower. Coincidentally, writing this essay parallels the novel, during the persistently unyielding summer of 2024. The story unfolds against a backdrop of extreme economic and social collapse. The government is weak, the environment is heavily polluted, and the gap between the rich and the poor is wider than ever. The protagonist, Lauren Olamina, lives in a walled community in California. She suffers from a rare condition called ‘hyperempathy’, which means she physically feels the pain and joy of others. The story reads as a warning about human-induced climate catastrophe: ‘People have changed the climate of the world. Now they’re waiting for the old days to come back,’ writes Butler.[1]

Water scarcity and pollution are significant themes in Parable of the Sower. Gale resides in California, where major floods occurred in 2022 and 2023, resulting in fatalities. Gale notes that water often drives the climate debate: whether it’s a shortage or an excess. The range of acceptable water levels for humans is very narrow. This fear of water fascinates Gale, as the artist mentions in an interview, because it reflects a very human-centric perspective.[2] Water, and the earth as a whole, are indifferent to humanity. With DRRRUMMERRRRRR, Gale confronts us with this reality: ‘Any fantasy that humanity may have about its future is circumscribed by the reality of rising sea levels and an increasingly hotter atmosphere.’[3] It is Gale’s response to the Western and patriarchal notion that the end of humanity equates to the end of the world.

DRRRUMMERRRRRR thus appears to be a counter-reaction to the Anthropocene, the term used to denote a new geological epoch in which human influence on the earth has become a dominant force in shaping the climate and environment. Besides the Anthropocene, there are many variations ending in ‘-cene’ to describe the current epoch: Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chtulucene.[4] Each of these terms draws attention to specific issues (such as capitalism, colonialism, or climate justice) and invites a different form of engagement. Additionally, in 2020, philosophers Donna Haraway and Vinciane Despret introduced the Phonocene: the age of sound. The term is described in Despret’s book Living as a Bird (2022), where she explores how birds experience and understand the world and what humans can learn from them. She describes how birdsong can remind us of the many sounds of the earth and the importance of listening to them. By naming our epoch the Phonocene, we are continually reminded of the significance of sound and its associated silence, writes Despret:

‘It means not forgetting that, if the earth groans and creaks, it also sings. It means not forgetting too that these songs are in the process of disappearing, but that they will disappear all the more rapidly if we do not pay attention to them. And with them will also disappear a multiplicity of different ways of inhabiting the earth, of the inventiveness of life, of arrangements, melodic scores, fragile appropriations, ways of being, things that matter. […] Living our era by calling it ‘Phonocene’ means learning to pay attention to the silence that a blackbird’s song can bring into existence; it means living in sung territories but also acknowledging the importance of silence.’ 10

Through the installation, Gale also urges us to pay attention to the sounds of a creaking and groaning Earth. Not the drum kits, but the sound of flowing water takes centre stage. It is, as Despret describes, the sound of the earth that will remain, with the drum kits serving as dystopian relics of a once human-inhabited planet.

And Don’t Call Them Lady Composers

Oktober/November

In the exhibition Open Field, artists Elsemarijn Bruys and Loma Doom (the pseudonym of Femke Dekker) pay tribute to female pioneers in electronic music, who laid the foundation for the art of listening. At the heart of their installation are two colossal mirrors that rotate on their own axis. These mirrors not only capture the visitor in their reflection but also reveal the surrounding space from constantly shifting perspectives. As the mirrors slowly turn, a layered soundscape unfolds. In five phases—each to be understood as an exercise in attentive listening—the legacy of influential composers such as Pauline Oliveros, Hildegard Westerkamp, Laurie Anderson, Éliane Radigue, and Yoko Ono is explored. These artists all share a special relationship with listening and experimented with it in their music, art, and performances.

In Open Field, Bruys and Loma Doom reflect on the 1950s and 60s, a period when electronic music flourished and female composers pushed boundaries by creating entirely new sounds or using innovative instruments. At the same time, they also draw a connection to the present by highlighting the influence of these pioneers on contemporary compositions and listening practices. In their work, movement, sound, and light come together, with a focus on the multi-sensory experience of listening. For Bruys and Loma Doom, the art of listening does not concern the ears alone but involves the whole body in the act of paying attention. This is also reflected in the exhibition’s title, Open Field, which references a 1980 sound exercise from Pauline Oliveros’ book Deep Listening: A Composer’s Sound Practice (2005), where this holistic, engaged approach to listening is central:

‘When a sight, sound, movement, or place attracts your attention during your daily life, consider that moment an “art experience”. Find a way to record an impression of this momentary “art experience” using any appropriate means or media. Share these experiences with each other and make them available to others.’11

The exercise invites you to experience every sight, sound, or movement as a work of art, and to share that experience with others. In the exhibition, Bruys’ kinetic practice merges with Loma Doom’s sound and listening art in an installation that encourages this approach and puts the exercise into practice. Loma Doom’s years of research into listening, particularly the role of female composers, is made tangible in Bruys’ scenography. In five rotating chapters, you are invited to retune your ears through listening exercises inspired by female composers who have been instrumental in developing these ideas about listening.

The (re)appreciation of female composers is not new. In 1970, Pauline Oliveros submitted an opinion piece to The New York Times titled, ‘Why have there been no ‘great’ women composers?’—echoing the famous question that art historian Linda Nochlin posed a year later in her iconic essay, ‘Why have there been no great women artists?’12 Both Oliveros and Nochlin arrive at the same conclusion: historically, women have simply not been given the same opportunities to rise to prominence as great artists or composers. Their education, motivation, or skills were seen as secondary to their role within the domestic sphere, according to these revolutionary thinkers. In her piece, Oliveros passionately advocates for a re-evaluation of female musicians and composers, emphasizing that men should play a key role in this shift. She argues that a woman in the music world can only be successful if she is exceptionally talented, whereas men with the same or even lesser talent are given opportunities. Moreover, Oliveros notes that female composers often face opposition, both overtly and through subtle forms of exclusion by their male colleagues.13

The indignation of Oliveros is entirely understandable, given that it was women who pioneered electronic music in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. 14 As with many ‘new’ and unexplored art forms, such as video art or performance art, it was often women who took the lead in developing and paving the way, because these emerging areas of the art world had not yet been dominated by men, nor had rigid rules and hierarchies been established. The freedom of a new medium fostered joy, experimentation, and the creation of works that are now considered groundbreaking. Composer Suzanne Ciani (1946) was asked in a 2020 interview about this period when female composers were actively experimenting, and she remarked:

‘I always say to women, if you want to be successful, find a place where there isn’t anybody else. I think for women, [electronic music] gave us independence. I studied classical composition, conducting, the whole thing, and it was a man’s world – and still is today, really, annoying as it is. But in electronic music, you could do the whole thing yourself. That’s what attracted women. This is a story of intimacy, in a way, with these machines.’15

Daphne Oram working at the Oramics machine at Oramics Studios for Electronic Composition in Tower Folly, Fairseat, Wrotham, Kent.

Nevertheless, many of these early female pioneers faded into the background or were forgotten. Director Lisa Rovner aims to change that with her 2020 documentary Sisters With Transistors. The film profiles several of these pioneering composers, highlighting how women expanded the boundaries of music using computers, synthesizers, and homemade instruments. 16 For example, the documentary features Clara Rockmore (1911-1998), a violin prodigy who enchanted audiences in the 1920s with her theremin, an electronic instrument played by moving one’s hands through the air instead of making direct contact. Delia Derbyshire (1937-2001) also appears, a British innovator whose career flourished in the 1960s at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop (Derbyshire is best known for her composition of the Doctor Who theme, created by cutting and splicing analogue tape). Or the aforementioned Suzanne Ciani, who in the 1980s composed music for desktop software and TV commercials but was unable to secure a record deal due to the biases she faced as a female musician. At one point, Ciani describes how she walked into a studio, where a male technician asked her, ‘Where do you want the microphone?’—he assumed she was a singer, rather than a keyboardist working with a complex electronic synthesizer. 17

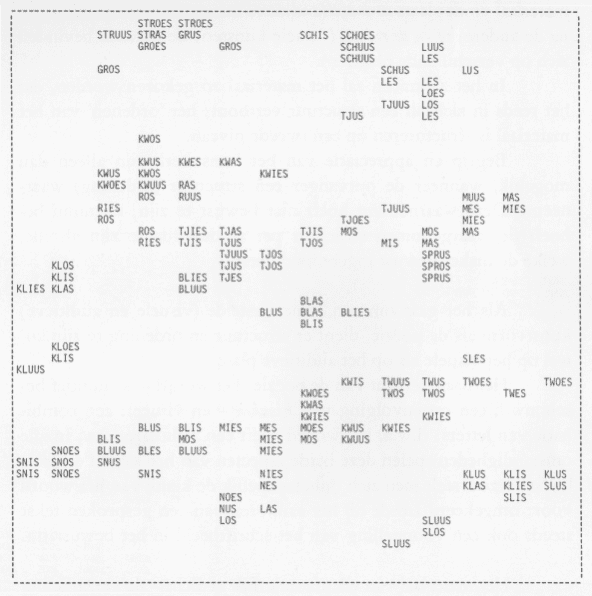

The documentary has a strong focus on the United Kingdom, but on the other side of the North Sea, women were also working to push the boundaries of (electronic) music. Greta Monach (1928-2018) studied the Dutch language in Leiden and flute at the conservatory in The Hague. These two areas of interest manifested in her immense passion for experimental sound poetry, where sound and language converge. Monach went on to work at the Institute of Sonology in Utrecht, where composers, technicians, physicists, poets, and artists collaborated. Monach became a pioneer in sound poetry—a performative art form centred around sounds, rhythms, and textures. A key component of her work is the so-called Automaterga poems: letter drawings generated by computer, which she then vocalised into sound. For Monach, this form of poetry made perfect sense: ‘Music is abstract, modern painting could apparently also be abstract, so why not poetry?’ she said in an interview.18

Greta Monach, automatergon 72 – 7 S, variant 2.

Monach’s contemporary Yoko Ono (1933) put sound poetry on the global map. Ono views this art form as a logical instrument for breaking down conventional boundaries of language, music, and art. On the album Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band (1970), Ono utilised her voice in a manner reminiscent of Monach’s sound poetry, using primary sounds, screaming, and singing without traditional melodies or lyrics. Ono experimented extensively with sounds and, like Oliveros, developed listening exercises for the audience. In 1964, she published the book Grapefruit, which contains various instructions that exist somewhere between a poem and a score. Some instructions are concrete—such as making a tuna sandwich—while others are more abstract and poetic. Many focus on sound: noticing, recording, or recalling certain, almost always everyday sounds.

The delineation or definition of disciplines was uninteresting to Monach and Ono, and this is something they shared with many of the groundbreaking, unconventional composers upon whom Bruys and Loma Doom build in their exhibition. It is a celebration of these women from history and their far-reaching influence on the present and future, but it also calls for reflection. How come that some of these women have been almost erased from collective memory? Bruys and Loma Doom invite this reflection very concretely with perhaps one of humanity’s most universal objects. Almost everyone has a mirror in their home, and in Open Field, this everyday object takes centre stage. The two mirrors in the exhibition have been enlarged to gigantic proportions and rotate on their own axis. This magnification provides a life-sized reflection of yourself, as well as your surroundings. Furthermore, it offers a glimpse of yourself within that environment. The installation raises your awareness of your position in the world and literally illuminates it from different perspectives.\

The alluring effect of seeing yourself in mirrors also explains the popularity of the mirror selfie: you can see exactly how you look while taking the selfie, but above all, you can provide a broader context of your surroundings, such as your bedroom, bathroom, or gym. It offers a true glimpse into your life. Perhaps the most famous mirror selfie in (art) history is Portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini and His Wife by Jan van Eyck from 1434. Upon closer inspection, you can see in the background of this double portrait a small, round mirror in which the artist has painted himself. According to many art historians, the artist thus places himself at the centre, rather than the portrayed subjects: art does not reflect life, but rather reflects the artist. The use of a mirror underscores this idea and directly involves the viewer in the work.

Laurie Anderson - Self-portrait into the edge of a mirror, 1975

In 1975, Laurie Anderson—an innovative artist who intertwines music, art, and performance in her work and who also serves as the narrator in Sisters With Transistors—created four self-portraits. In the photographs, her face is partially visible, with part of it cut off by a mirror. In the mirror, one half of her face is reflected, creating a disorienting effect. As in all her work, Anderson constantly oscillates between her true self and an artistic or artificial persona. Her self-portraits precisely reflect this split between what is and what could be. This is exactly what Bruys and Loma Doom aim to convey in their exhibition. Every movement, every reflection, every sound can become a work of art, provided you view it in that way. Listening as an open field, in which listening is continuous, dynamic, and collective, fostering interaction with others. Both the viewer and the environment are incorporated into this experience: a true self-portrait of the world.

1 Pauline Oliveros, Quantum Listening (Ignota Books, 2022) 30.

2 Pauline Oliveros, Quantum Listening (Ignota Books) 30.

3 Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2015) 24.

4 Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2015) 157-158.

5 Nikita Gale discusses this book in episode 1 of the podcast Instead of “sound art,” say: abrasion, a dirge, willed from the other side of a leaky room, undisciplined, celebrative, dangerous, always emerging, published by Overtoon – Platform for Sound Practitioners on 15 February 2024.

6 Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Sower (New York: Seven Stories Press, 1993) 23.

7 Essence Harden, ‘Nikita Gale investigates material to discover new possibilities.’, Art21, <https://art21.org/read/in-the-studio-nikita-gale/>.

8 Nikita Gale, HOT WORLD statement, 2019.

9 The term Capitalocene is a portmanteau of ‘capital’ and the Greek word ‘kainos’ (new), introduced by American sociologist and geographer Jason W. Moore. It highlights the role of capitalism as the driving force behind the major ecological changes and environmental degradation we are experiencing today. The term Plantationocene has also been popularised by philosophers Donna Haraway and Anna Tsing, and it emphasizes the impact of plantation systems on ecology, economy, and social structures. These systems are characterized by monoculture, labour exploitation, and extractive practices that harm both the environment and people. The Chtulucene, a term coined by Haraway, underscores the interconnectedness of all living beings and the importance of collaboration, symbiosis, and sharing worlds.

10 Vinciane Despret, Living as a Bird (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2022) 160-161.

11 Pauline Oliveros, Deep Listening: A Composer’s Sound Practice, 2005 (New York: iUniverse) 42.

12 Pauline Oliveros, ‘And Don’t Call Them “Lady” Composers’, The New York Times, 13 September 1970.

13 Pauline Oliveros, ‘And Don’t Call Them “Lady” Composers’, The New York Times, 13 September 1970.

14 Aimee Ferrier, ‘How electronic music gave women a pioneering platform’, 3 June 2023, Far Out Magazine, https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/how-electronic-music-gave-women-a-pioneering-platform/.

15 El Hunt, ‘Electronic Ladyland: why it’s vital we celebrate the female pioneers of synth’, 6 November 2020, NME Magazine, https://www.nme.com/features/female-synth-pioneers-design-museum-electronic-ela-minus-kelly-lee-owens-2810809.

16 Nevertheless, Sisters With Transistors also has gaps. There are no interviews with musicians of colour, nor are there references to the Black and queer-driven electronic dance scenes that emerged simultaneously and had a significant impact. Additionally, Wendy Carlos (born 1939) is surprisingly featured only briefly, despite being the only trans woman in the film and likely the most well-known for her music. Carlos released the groundbreaking album Switched-On Bach in 1968 and gained recognition as a film composer for A Clockwork Orange, The Shining, and Tron.

17 Lisa Rovner, Sisters With Transistors, 2020.

18 Hans Heesen, ‘Ik dacht je moet dat veel radicaler benaderen’: op bezoek bij ‘sound poet’ Greta Monach’ 2018.