Listen in every way possible, to everything that is possible to hear (Part IV)

- Eva Burgering

In May 2024, Nest moved into its new home in the Laak district of The Hague. It feels increasingly more like home: the concrete walls with cracks and blackened imprints (testaments to artistic experiments by previous inhabitants), the cars rushing past on Calandplein, the practical advantages of having a hardware store next door. It is a place where Nest programs, displays, questions, and experiments with joy. Several times, Nest has also opened its doors at night during Club Laak’s club nights. Partygoers enjoyed exhibitions by Nikita Gale, Elsemarijn Bruys, and Loma Doom well into the early hours, with a pleasant mix of naturalness and wonder.

Cathedrals of Gentrification

December 2024 –January 2025

One person who shares this sense of inevitability when it comes to art in nightlife is Joeri Woudstra. As one of the founders and programmer of the club, he knows the spaces inside out. For him, the question is not whether art can exist in the night, but how it can (and why not more often?!). At the same time, Woudstra does not shy away from asking critical and curious questions about the relationship between experimental spaces like Club Laak and Nest, and processes of gentrification. His curiosity about the various roles a nightclub can play in a city – both as a warm-up for property investors and as a hedonistic refuge – is reflected in the works he created for the exhibition at Nest in Laak.

However, Woudstra did not work alone on the exhibition Thin Air: You’re Gonna Carry That Weight. The British artist Hannah Rose Stewart and Woudstra met years ago in a club in Berlin and decided to combine their shared fascination with nightlife, pop culture, and gentrification in a duo exhibition. In her work, Stewart deftly captures the zeitgeist of her generation, the millennials. Her sculptures, films, and installations are imbued with nostalgic imagery and hyper-contemporary references to pop culture. For both Woudstra and Stewart, large themes intersect in nightlife: feelings of nostalgia, popular culture, capitalism, and processes of gentrification. Architecture and scenography play a significant role for them in creating a particular atmosphere in which these themes can be questioned. Together, the artists transform the space of Nest in Laak into an unheimlich backstage club space where the boundary between inside and outside is blurred, the sacred and the everyday go hand in hand, and recognition and alienation alternate as the dominant forces.

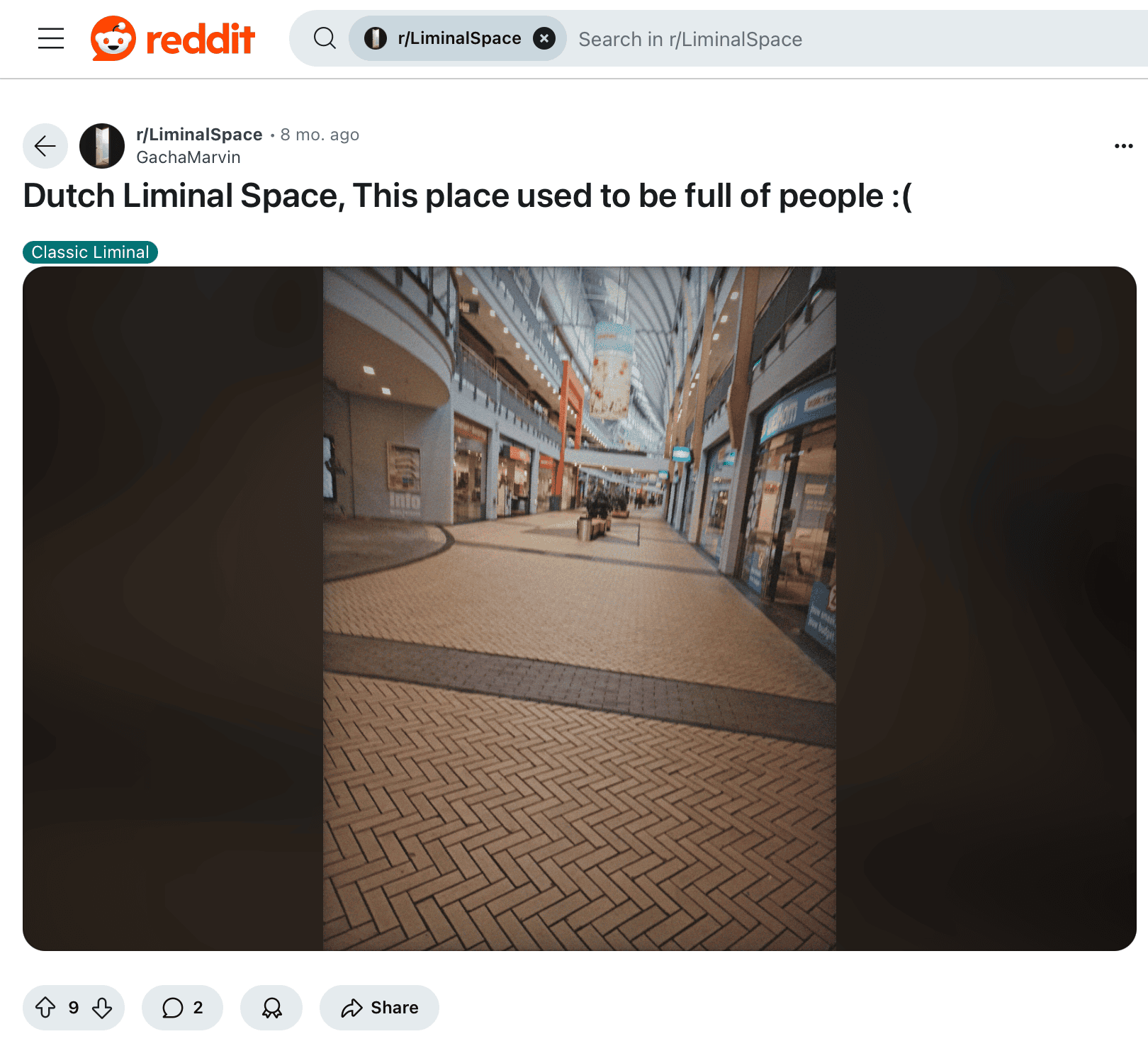

A key concept in the exhibition is that of the so-called liminal space. An empty hotel corridor, an abandoned office, a neglected gas station: these are all examples of places that can be seen as liminal spaces. Liminal spaces are a typical example of an internet phenomenon that gained prominence around 2019 through online platforms like Reddit. The subreddit r/LiminalSpace has about 760,000 followers and is a webpage where people share photos of these kinds of places, described on Reddit as a space that exists between ‘what was’ and ‘what is to come’: “It is a place of transition, waiting, and not knowing. Liminal space is where all transformation takes place.”1These places capture the imagination: they seem familiar to us, even though we’ve never been there. They are spaces intended to be used, to pass through, but never to stay in for long. These (abandoned) shopping malls, parking lots, or airports evoke both discomfort and nostalgia. What they have in common is the lack of people. But unlike images of nature, they do contain a clear imprint of human presence.

It is this absence of people, a so-called ‘failure of presence,’ that according to cultural theorist Mark Fisher, makes liminal spaces both eerie and intriguing or beautiful. Fisher, known for his book Capitalist Realism on the dominance of the capitalist system, sees liminal spaces not as physical places but rather as symbolic spaces where the boundary between the past, present, and future fades.2 Liminal spaces, according to Fisher, can evoke feelings of melancholy, alienation, and loneliness, which he links to the idea of hauntology – a concept borrowed from philosopher Jacques Derrida. In our current age, the ‘hauntological’ time, we are haunted by the lost possibilities of other social systems that never came to fruition. Liminal spaces, therefore, are zones or places (both physically and mentally) in which these feelings of loss and missed opportunities manifest.

This failure of presence also exists in the area around Nest itself. Anyone googling for ‘liminal spaces the Hague’ will stumble upon a Reddit page titled ‘Dutch Liminal Space, This place used to be full of people :(’ with a blurry photo of an empty shopping mall. It is a photo of the Mega Stores in The Hague, the indoor shopping mall that is next to Nest in Laak. The Mega Stores opened its doors in 2000, American-style, with the promise of becoming a major success. But visitor numbers soon fell short, and many stores became vacant. By 2024, demolition has been scheduled for large parts of the mall, which are to make way for new housing. In addition to the liminal spaces that now exist in the complex, other (temporary) uses have been found for the vacant buildings, such as Nest itself or Club Laak. It is an interesting interplay between culture and urban development: clubs and cultural institutions are often rooted in old industrial buildings, warehouses, or other non-traditional locations that, within urban development, are seen as undesirable. They ‘warm up’ the neighbourhood, making an area more attractive to live in. In this way, these kinds of initiatives contribute to gentrification, a process in which price increases can drive out original residents and businesses from their neighbourhood.

Reddit page about liminal spaces in the Netherlands.

For Woudstra and Stewart, nightclubs are therefore seen as ‘cathedrals of gentrification.’ This sacred reference fits well with the concrete cube of Nest in Laak, where the acoustics are reminiscent of a high church or cathedral. On the stands of Nest, RADIATE is installed, Woudstra’s monumental organ built from speakers. The work functions as an altarpiece in the exhibition, with Woudstra’s soundscape emanating from it. Woudstra based the composition on what he calls the ‘musical backdrop of capitalism.’ By this, he refers to music that plays in the background while emails are being sent, music playing on the radio in a coffee shop, or music accompanying content while scrolling through social media feeds. In other words: music over which you have little control, which seeks you out through all possible channels instead of the other way around. The soundscape mixes, slows down, or speeds up his own compositions, ambient tracks, and popular pop music from artists like Charli XCX. In addition to RADIATE, Woudstra crafted a glass piece and a streetlight, subtly drawing the outside in with an unsettling sense of alienation. The glass piece is lit from behind, evoking the stained-glass windows of churches.

The organ and glass piece are extended by Stewart with a series of sculptures: a podium piece, a tiled sculpture, an LED ticker. Together they form a scenography with a specific atmosphere. The artists seek to recreate a liminal space within the nightlife: the backstage of the club, where the party feels near, yet remains just out of reach. They see the liminal spaces of nightlife not only as the abandoned buildings serving as nightclubs, but also as transition spaces between nightlife destinations, such as when you walk from one club to another in the night. The exhibition by Woudstra and Stewart thus leans on the same immaterial dimension that liminal spaces have; on a feeling, an atmosphere. The feeling of melancholy and nostalgia that you can feel throughout your body, that sometimes overtakes you when you hear a song, see an old photo, or find yourself in a particular place. These nostalgic feelings are deeply personal and will vary for each person depending on their personal history, memories, and experiences. However, for Stewart and Woudstra, there is also a strong generational nostalgia that they address in the exhibition. Difficult to capture in words, but all the more so with sound, an overall scenography, and small references and symbols.

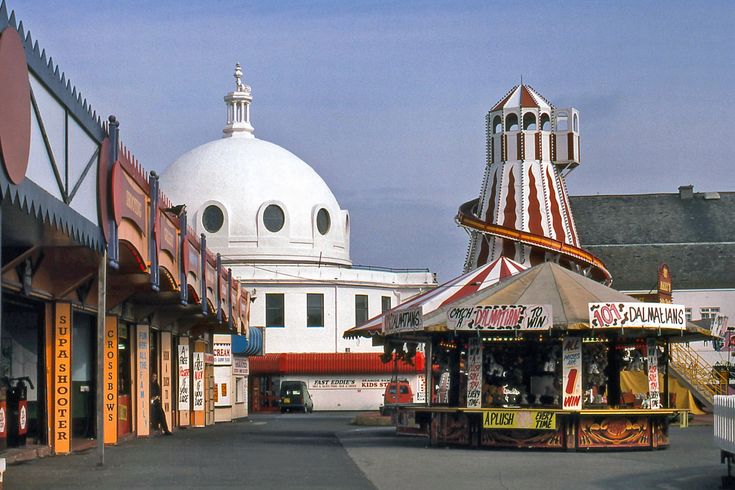

Spanish City in Whitley Bay.

In one of Stewart’s sculptures, for example, the logo of a Victorian-style British pub is displayed. It takes her back to the seaside town where she grew up, where countless pubs like this exist: Whitley Bay. On the outskirts of Newcastle, Whitley Bay was a thriving resort town in the last century. When air travel became available to a larger group of people, British tourists stopped visiting their own coast and instead headed to warmer countries. Whitley Bay became a typical sleepy seaside town for the working class, with decaying tourist attractions. The symbol of this is Spanish City: an amusement park that opened in 1905 and was once the height of wealth and entertainment. In the 1980s, the band Dire Straits even dedicated a song to it, Tunnel of Love: “Oh, like the Spanish city to me – When we were kids – Yeah, girl it looks so pretty to me – Just like it always did.” After Spanish City closed in 2000, it quickly deteriorated and became a deserted theme park beloved by young people for drinking. For Stewart, it is these kinds of desolate places that symbolise her childhood. Liminal spaces, soaked in nostalgia, awaiting transformation or new use, and in the meantime hovering between the past, present, and future. They belong to no particular history – because they still exist – but they also don’t feel contemporary or futuristic.

In addition to the references to her youth in Northern England, nightlife is also a prominent feature in Stewart’s work. For her, nightlife reflects how people interact with one another. It shows the challenges within society, but at the same time provides a space where people can support each other and come together in solidarity. This approach to nightlife is also evident in the 2018 documentary Everybody in the Place – An Incomplete History of Britain 1984-1992 by artist Jeremy Deller, where he places the rise of club music such as rave and acid house at the centre of the profound social changes that took place in the 1980s.3 In the documentary, Deller gives a guest lesson in social studies to a class of Generation Z students in London. He explains how club culture emerged from Black communities in the UK, leading to raves and parties that transcended class, identity, and geography. He also links club culture and dance parties to the political history of the country, for example, by drawing connections to the miners’ strike of 1984-1985. The emerging club scene caused as much upheaval in the country as the protests did.

That the club and underground scene has roots in Black communities in the United States and the UK is not always acknowledged today. For instance, within the techno genre, which originated in Detroit with pioneers like Jeff Mills, this origin is often erased, a process known as the ‘bleaching’ or ‘whitewashing’ of techno.4 Techno festivals such as Awakenings in the Netherlands have for a long time had almost entirely white (and male) DJ line-ups, although this has thankfully started to change in recent years. This shows that club culture and raves cannot be detached from society. Nightclubs are often seen as ultimate sanctuaries of freedom—places where you can truly be yourself and escape into a parallel universe, untouched by the demands of work, school, or everyday concerns. Yet, isn’t a club also a microcosm of society, evolving with the times and mirroring the same social norms, values, and challenges?

It is the contrasts within this micro-society that Woudstra and Stewart highlight in the exhibition. Day and night, the past and the future, the ordinary and the sublime, inside and outside, the decayed and the brand new. Are these contrasts truly irreconcilable? In the twilight that envelops Nest during Thin Air: You're gonna carry that weight, these stark opposites sometimes merge or flow into one another. Woudstra and Stewart reshape the exhibition into a liminal space, inviting the audience to lose themselves in these transitional realms—both physically and mentally.

1Reddit, ‘r/LiminalSpace’, <https://www.reddit.com/r/LiminalSpace/>.

2 Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures, 2020 (Londen: Zero Books).

3 The documentary Everybody in the Place – An Incomplete History of Britain 1984-1992 (2018) by Jeremy Deller is available to watch in full on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jqc_1NVHE-0.

4 Seb Harris, ‘The Bleaching Of Techno: What White People Must Learn’, oktober 2020, FOCUS Magazine.